“The test of a work of art is, in the end our affection for it, not our ability to explain why it is good.”

Stanley Kubrick

Criticizing, comparing, and understanding the infinitely complicated children of a genius is not an easy task, let alone the children of two geniuses. And so here I am on a Saturday, two weeks after a careful reading of William M. Thackeray’s novel, The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq., unsure what to write. So here I am on a Saturday, after a dozen viewings of Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon, one of my all-time favorites, unsure what to write. I am not qualified to tell you about the technical marvels of the film, nor am I an actor or photographer. And still, as a writer, it is not easy to tell you what the novel has in store. But Kubrick really throws me a bone with that quote, “Just do your best,” he seems to be saying. And so I will, even if it comes down to stating my simple affections.

I think it is best to start this week’s review where the film began, with the novel. A dusty old Oxford World Classic, one might see the iconic white stripe on the cover, remembering that some horribly boring poetic dialogue they read in high school belonged to the same banner. But it shouldn’t be judged as such for it’s actually terribly approachable and entertaining like much writing of the same time period.

And believe me, like anyone, I was once intimidated by the ridiculous language, silly costumes, hideous makeup, and stern rules of those centuries; I suppose, until I was forced to read of them. What I found then was that I had been missing out on a miracle: two hundred years later we’re hilariously similar. Thackeray’s characters use the term “I O U” and love gambling, drinking, drama, and sex just like the rest of us. Mozart was into flatulent humor. Perhaps the industrial centuries are where we should draw the line between the humanity of old and new because it’s just too easy to see this novel played out today. Many of my old assumptions turned out to be false too. There is hardly any language barrier and the costumes are no more ridiculous than what you would see on the red carpet.

So I have no choice after that rant I guess, at the risk of greatly underestimating a critically acclaimed novel, but to try and sum it up. While Thackeray, according to the back cover, viewed the “true art of fiction” as “[representing] a subject, however unpleasant, with accuracy and wit, and not [moralizing],” you’re very likely to read it as a Christian novel. Peasant Redmond Barry, the protagonist and narrator, is far removed from the Irish gentry but clings onto the idea of his high birth. Barry’s pride, ambition, greed, adultery, and boldness takes him through several intense pistol duals, the seven years war, and to the top of every European court. The same qualities also become his tragic downfall as he tries to obtain a title of nobility and struggles to gain the affections of his snobbish pain-in-the-ass stepson, Lord Bullingdon. So you see, it’s pretty likely to read as some sort of Christian admonition or a novel of the seven deadly sins, like Crime and Punishment.

But Thackeray really does leave you to judge the moral of the novel. Indeed, it cannot be ignored that the protagonist is far from a Christian and all events are retold through his justification and narration. What’s sure though, is that by the end I was affected by the humor and grief and was glad to have it in my library.

Now, I’m sure by this point you are ripe to know how my tirade ties into the movie. Well, I am reminded of something Seneca wrote to Lucilius,

“What an indisputable mark it is of a great artist to have captured everything in a tiny compass“

Seneca, Letter LIII to Lucilius

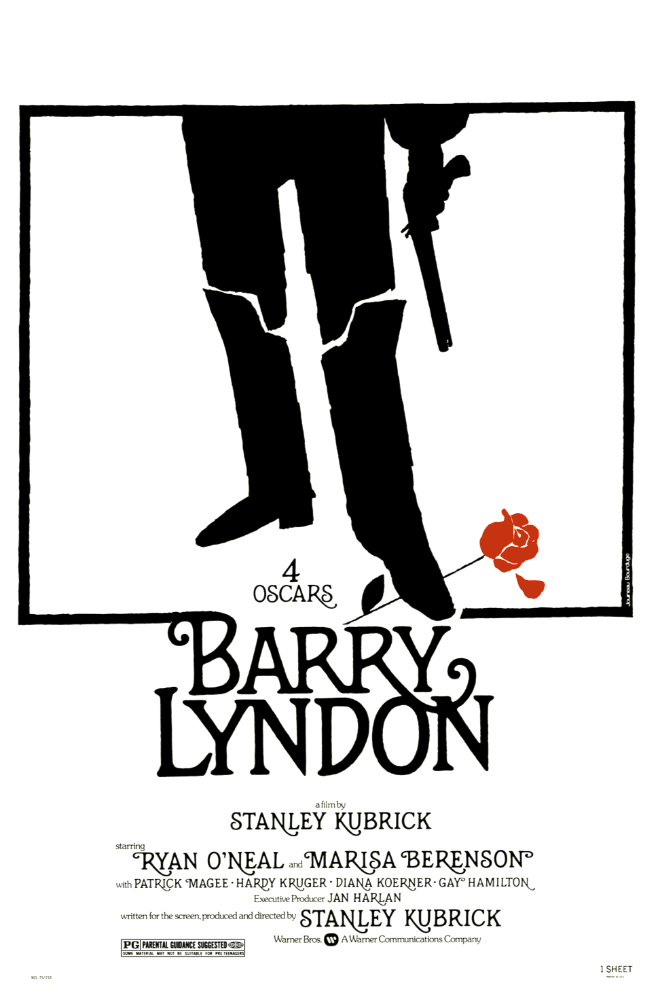

If the novel isn’t for you, the film surely is. Few people want to sit down and painstakingly read a novel they have no stake in (unless you’re a huge Kubrick and Barry Lyndon fan like me). As that fan, I will tell you that Kubrick makes the novel even more approachable and faithfully captures just about all of it in his compass. I mean every bit of dialogue is taken directly from the book and there seems to be hardly a piece of that novel missing. Yet, how much more the beautiful set pieces, camerawork, and acting represent than ten novels ever could. For all that, it feels like this movie is highly underrated and forgotten. Upon its release it won 4 Oscars, but today Kubrick is more well known as a skilled adapter for 2001, The Shining, and A Clockwork Orange. He ought to be remembered by this.

I have heard three YouTube essayists call the film a collection of renaissance paintings. Let’s not forget that it is also an entire novel and, like those other adaptations, a testament to the flexibility of the movie as a medium. It is infinitely inspiring and all for less time and money than a paperback oxford world classic. If you want to see the full potential of film, I love this work of art and I hope you will too.